When will the next general election be? No one knows. Well, perhaps Rishi Sunak does; the Prime Minister not-so-helpfully said he had a ‘working assumption’ that it would take place in late 2024.

As it happens, this will be a busy year in politics. Americans will also be going to the polls – the first time our two countries’ electoral cycles have synced since 1992. Already, there have been warnings about global disinformation campaigns – fuelled by AI and spread on social media – and what they may do to our already fragmented countries.

In total, over 60 nations – from India, Pakistan and Mexico to Taiwan and Ukraine – will be going to the polls before the end of 2024. Just under half of the world’s population is eligble to vote in some form of election this year, making it the biggest year for democracy in history. The world may well be a very different place by the time 2025 comes around.

In the UK’s case, at least, it feels like it has been a long time coming. The Conservatives have been in power for just under 14 years. Our last election was in 2019, but it feels like a lifetime ago. The pandemic was yet to reach our shores, Jeremy Corbyn was leading Labour, and Boris Johnson was Prime Minister.

FIND OUT MORE ON ELLE COLLECTIVE

Did you even vote for Johnson? If you’re reading this, it is statistically unlikely that you did. In 2019, 64% of women aged 18-24 and 54% aged 25-34 voted Labour. The numbers get a smidge narrower for the age group above that, but not by a huge margin. The last election was a disaster for the opposition, but would have been an annihilation event had it not been for young women.

Much has changed since then – Keir Starmer has replaced Corbyn, Sunak took over after a brief Liz Truss interlude – but one thing hasn’t. Women of working age remain a large voting bloc, and must be appealed to by parties hoping to win or retain Number 10. According to a study run by the Women’s Budget Group last October, 25% of female voters are still undecided, compared with 11% of their male counterparts. Does this mean it’s all to play for? Well, not exactly.

'In the 20 years following World War II, women were more likely to vote Conservative,’ says Rosie Campbell, director of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. Britain was, at the time, in tune with many other democracies, but became an outlier in the 1980s, as women refused to follow the leftward turn of their counterparts in America, where single women, with or without children, found that Republicans didn’t cater to their economic interests. ‘In the US, a gender gap emerged, with more women voting for the Democratic candidate, and that became a bit of a global phenomenon, with many countries seeing the trend of women moving to the left of men. But it didn’t happen here in the UK until the 2010s,’ Campbell adds.

There are some hypotheses as to why that was the case – women were more religious and less likely to encounter the union movement at work – but none are entirely conclusive. As research run by think tank The UK In A Changing Europe found: ‘prior to 2010, gender gaps were small, but by and large women were more likely to vote Conservative than men, and men were more likely to vote Labour than women’. The trend has slowly been reversing, driven especially by Britain’s exit from the European Union, as younger women in particular were more likely to be strongly opposed to Brexit.

The Conservatives have, so far, failed to find a way to win them back, as their priorities still aren’t matching up. As Campbell says, ‘The big issues that seem to be driving young women to Labour are concerns about the cost of living and concerns about the NHS. A focus on immigration is going to be much less significant for them.’ Awkwardly, the Conservatives are also failing to find a way to keep the male voters who backed them at the last election. The overall story now is that it’s the same for all genders, an analysis that chimed with the conversations Jess Phillips, Labour MP and former shadow minister for domestic violence and safeguarding, has had with voters. ‘In this period, more than ever before, [people’s priorities] have become uniform, and that is because of the cost-of-living crisis’, she says.

‘It’s not so much that women have changed – they’re exactly as they’ve always been, caring about their ability to run families and households and being able to afford things, but now many more men will talk to you on the doorstep about the cost of their electricity bill.’ As she sees it, it’s probably good news for her camp, as ‘the problem with the Tories is they can’t make promises on that, because they haven’t been delivering’. Because the Conservatives struggle to make a positive case for their record on the issue, they have instead been focusing on other policy areas, namely the ‘small boats’ crisis and the government’s plan to send refugees to Rwanda. It just isn’t clear that it will help the party reach women voters. Still, this isn’t anything new. Since the Brexit referendum, much of mainstream politics has been aimed at relatively narrow segments of the population. ‘The narrative we’ve had in the last few years has been about men in left-behind constituencies,’ Campbell says.

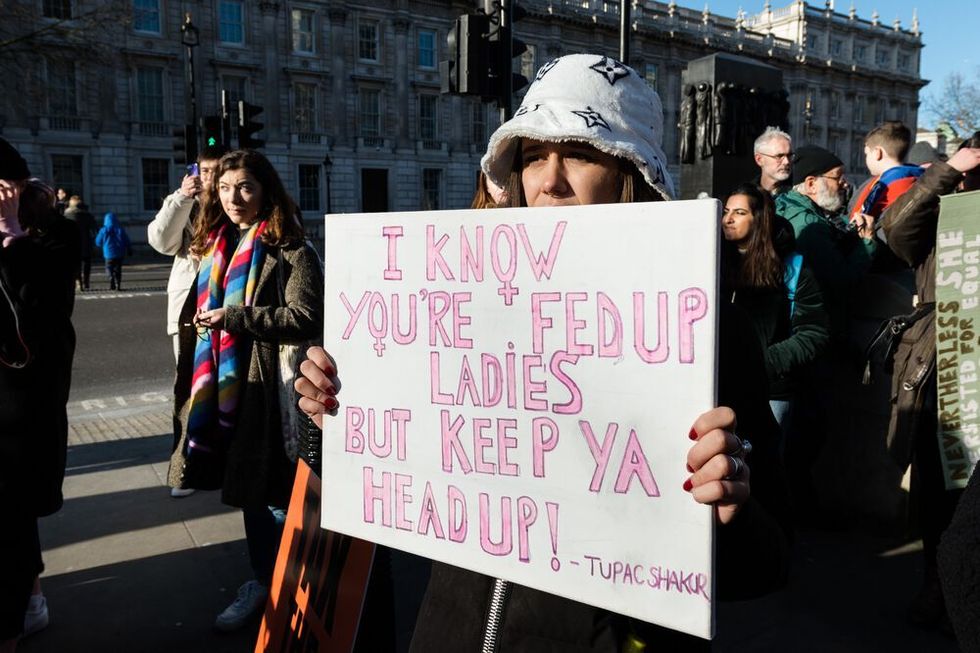

‘It hasn’t always been explicitly stated that the parties were fighting for men’s votes, but I think they were. The narrative was very much around the “white-van man”, and women were left out of the conversation,’ says Campbell. It was and remains a frustrating state of affairs, as, ‘on average, women are more economically vulnerable, more likely to be in low-paid, insecure work’. On the bright side, things seem to finally be changing, with at least one party noticing that women form over half the electorate, and ought to be appealed to.

In a report last year aimed at the opposition’s leadership, the think tank Labour Together wrote about the party’s path to power. According to it, a Labour party hellbent on gaining power should be focusing on the voter it named the ‘Stevenage woman’. ‘She, and voters like her, live in towns and suburbs across the country. Young, hard-working but struggling to get by, she feels that national politics makes little difference to her life and her town. Her attitudes aren’t dogmatic, leaning a little towards social conservatism and a little towards a more interventionist state,’ the report says. ‘Stevenage woman’ doesn’t vote in every election and, when she does, will oscillate between parties. Though it is possible that she voted Conservative in 2019, she is now more likely to swing towards Labour. She is, in a way, reminiscent of New Labour’s ‘Worcester Woman’, who was targeted by Tony Blair in 1997 and 2001. On one hand, this feels like progress, even though we are merely returning to what parties knew they had to do two decades ago. Some policy areas for women, like childcare, are now being taken more seriously than they were in previous parliaments. Annoyingly, it doesn’t mean that much is necessarily about to change.

‘We had the budget at the start of the year and the injection of money into childcare in England was very much welcome,’ said Carole Erskine of the campaigning group Pregnant Then Screwed. ‘As time has gone on, and the details have come out, those who deliver childcare have expressed quite a lot of reservations about the amount of money. ‘It might actually make the situation worse, because the expectation from parents is that, from next year, there will be a big jump in the amount of funded hours available when, actually, providers are saying that they can’t deliver that with the money that’s there,’ she explains. ‘Childcare has come to the forefront of decision-makers’ minds, but it has not been thought through, and the government and all parties aren’t really working with the sector to make sure that they’re putting enough money in so these schemes are viable.’

Similarly, Women’s Equality Party co-founder Catherine Mayer isn’t exactly optimistic about what’s to come. ‘Women were hit harder in many ways by the pandemic, and now they’re supposed to shoulder the cost-of-living crisis as well,’ she says. ‘This should be a time to actually cut through this and say, “Look, we recognise that these things have fallen unequally, and we recognise that there are times when it’s necessary to front-load investment in order to get a very, very quick and very high return,” which you would do with universal free childcare. Instead, we’ve just got Keir Starmer trying not to

scare the horses.’ Because the Labour party lost four elections in a row, it is now campaigning with the demeanour of someone walking on thin ice. It may be a clever thing to do, as the polls do show that the party is on track to win a large majority, but some worry that it won’t be bold enough when in power. Britain’s public services are in a dire state, and big thinking and even bigger policies will be needed to make sure that the country gets back on track. As Philipps says, ‘people are grateful for very little at the moment’.

Is Labour’s front bench aware of the scale of what’s at stake? Anneliese Dodds, the shadow secretary of state for women and equalities, thinks so. ‘Women just want to get on with our lives, don’t we? Knowing that we’ve got financial security, that we can get an NHS appointment when we need to, not having to worry about the threat of violence. Currently, our country is failing on all of those fronts,’ she says. ‘When it comes to the cost of living, on average, women are £1,200 worse off per year now than they were in 2010. For women in their thirties, that figure rises to £4,000.’ The ‘motherhood penalty’ – the pay gap between working mothers and women without children – is arguably the root cause of the shocking figure. In order to fix this, Labour say they would introduce policies including free breakfast clubs for every primary-school child and policies prompting businesses to create menopause action plans. Dodds, shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves and Baroness O’Grady are currently working on a pay-gap review together. As for the Conservatives? Well, it’s hard to say. I was told I could have some time with Kemi Badenoch, the secretary of state for business and trade and president of the Board of Trade, who moonlights as women’s minister, but nothing came of it. What will they focus on? They wouldn’t say.

Looking at their recent record, it is likely the Tories will point out that the party has now had three female leaders, while Labour has had none. Both Sunak and several of his ministers have previously spoken about violence against women and girls, and may keep promising to tackle the problem. In 2022, the government introduced a rape and sexual-abuse helpline. Another area the Conservatives are likely to try to play for is the debate over trans rights, since the party opposes self-identification, as well as most cases of social transition for teenagers. But this strategy is unlikely to work. 2022 research from civic non-profit More In Common found that Britons rank ‘the debate about transgender people’ as the least-important issue facing the country today out of 16 possible choices, and the party has already seen strong opposition from the trans community, led by activist Munroe Bergdorf who said she was ‘no longer willing to live under an authoritarian government’ run by a Tory party ‘intent on reducing trans people to second-class citizens’.

Back towards the centre, the Liberal Democrats do have some ideas to win over women voters. Last year, the party pledged to end ‘period poverty’, and adopted a policy aiming to ‘transform parental leave and early years education’ by boosting investment in the sector. Over the border, the otherwise-embattled SNP is likely to point out that it had the first gender-balanced cabinet in the UK. Looking ahead, it will promise to set up and implement a Women’s Health Plan, ‘aiming to improve services and reduce health inequalities for women and girls’.

Finally, the Greens arguably have the most comprehensive set of policies aimed at women – covering everything from pensions and company boards to abortion, crisis centres for rape victims and maternity laws – but they are, according to the latest data from Ipsos, polling at 9%. In short, most political parties are coming to terms with the fact women exist, but many could be going further to support them. They can still turn things around if they want to, given women are more likely to make up their mind nearer to election time. Because, after all, they can’t win without us.

ELLE Collective is a new community of fashion, beauty and culture lovers. For access to exclusive content, events, inspiring advice from our Editors and industry experts, as well the opportunity to meet designers, thought-leaders and stylists, become a member today HERE.